|

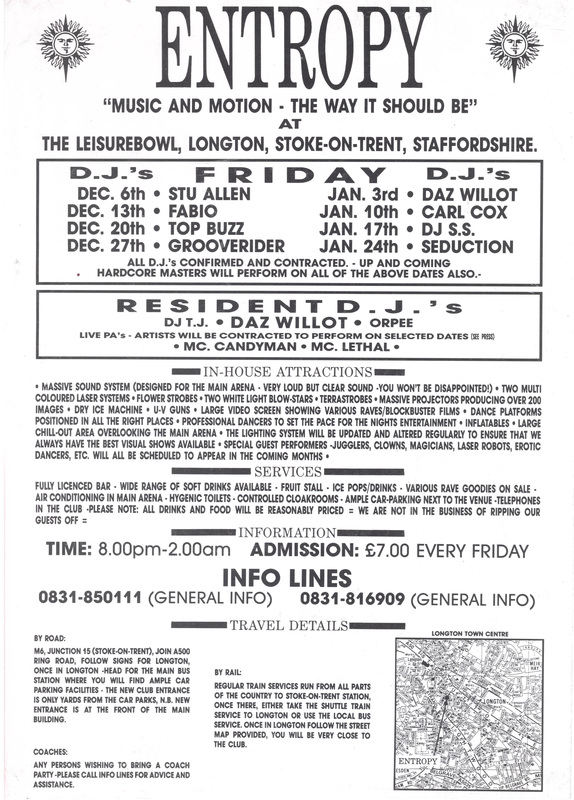

‘What we’re gonna do here is go back, way back’ (Todd Terry sampling Jimmy Castor) At some point around 1990/1, I began to spend less money on gig tickets and more on club entry. I’d was a buyer of vinyl, an NME reader, and travelled across England for hip hop and indie gigs. I was still rooted in or perhaps stuck on a working-class peripheral estate in Stoke-on-Trent, but I had escape routes. Weekends had always been dull for me as a 16-year-old, either drinking in the Miners’ Welfare Club where my step-father drank – avoiding the bingo and the covers bands – or going to some straight disco for pop hits. The occasional trip to see bands like Public Enemy and Pixies turned into a weekly habit of dancing to house and techno, in Stoke and further afield. By the time I left Stoke at 18 – for what I thought was for good – I was fully embedded in a house/ techno club culture, and stayed with it (in Cambridge and London) for the next decade, doing a bit of DJing, promoting, working in record shops, and a lot of staying up all night. What I didn’t know, at the start, was that Stoke had seen it all before. At some point, when my step-father’s friend Jack heard I was going to all-nighters, he started talking about the Torch, Tunstall and the Northern Soul events of twenty-years before. There, in the working mens’ club, sat a group of working-class men, who had worked in the mine that had closed in the 80s, or been ‘metal bashers’, but had been laid off in their 40s and never worked again, all on the sick. They would casually use racist epithets, but at the same time one of their number was black, and they would be drinking weak beer day after day, night after night, playing dominoes, cribbage and sometimes darts. It’s easy to see this place in one-dimension: they were the ‘left behind’ in 2016 parlance, and fit all the stereotypes of the lack of education, unthinking sexism, racism, homophobia, lacking interest in politics and culture beyond ‘the village’, the semi-derelict mining estate where we lived. However, even some of these people had been players once, before settling down. I’d even fell for these stereotypes myself, to some extent, changing the signs on the way in to Stoke to say ‘culture free zone’, on a visit back from university (where I’d found far more culture): Perhaps some or all of my academic work has been to repent for this. On joining the middle class (however tentatively), I kind of turned my back on the city, never visiting my family, losing touch. It was only after the city’s supposed turn to the far right, when my own estate had a BNP activist as chair of the residents’ association, that I started to go back as a researcher. I spent time there with groups working with refugees and white teenagers who skipped school, and with the far-right and radical Islamist groups that gave the city a bad name. What I’ve tried to do is show how the stereotypes of place, be it ‘white estate’ or ‘Asian streets’, and the association with poverty, backwardness, intolerance, are never the whole story. As I saw in the working men’s club, racism can be in the same body as a welcome to the ethnic other, a memory of flourishing youth culture in the same place as day-in/day-out boredom. Is Stoke a city of no culture, or was it ever? My plan, then, is to revisit this through questions about Northern Soul, techno and rave, Stoke-on-Trent, and Detroit. For a year, the Golden Torch was a key part of the Northern scene, and around two decades later Shelley’s was a key part of the rave scene. Both times, the local authority closed down the venues, although the scene lived on elsewhere. In both, much of the music emanated from black artists in Chicago and Detroit. The first time around a Stoke-based designer took Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ 1968 Black Power salute to create the logo above. The second time around, Staffordshire’s Neil Rushton (and involved both times) solidified a genre with a compilation of Detroit-based tracks under the name Techno: The New Dance Sound of Detroit. Stoke-on-Trent, the BNP’s ‘jewel in the crown’, embraced Afrofuturism, in the sounds of the Belleville three, and then in the British sounds of hardcore and drum ‘n’ bass. Necessarily, this embrace must be seen in the context of industry and later de-industrialisation, and the sound of a city’s machines becoming quieter. The jobs in heavy industry, in Detroit and Stoke-on-Trent, declined from the 70s onwards, and by the late 80s the machines were becoming ever more automated. Derrick May (Mayday) is quoted on the sleevenotes of Techno as saying that ‘black people no longer care if they never work again’, and that was just as true for the middle-aged men in the working men’s club. The few people left in the pottery factories were often reduced to pressing a button. So why this music? The first time is often associated with one form of adolescent escapism, with the optimism of emancipation in soul music and the joy of the dance being in contrast to the drudgery of the factory floor, and the bleakness of the industrial landscape. The second time, however, was an entirely different form of escapism. For Simon Reynold’s it was a nihilistic withdrawal from the de-industrialising city, with few jobs and no alternatives. Techno itself was birthed from a ‘broken promised land’ (Albiez 2005): did we in the UK’s midlands and northern cities hear the music, and know?

0 Comments

|

Archives

May 2022

Categories |