|

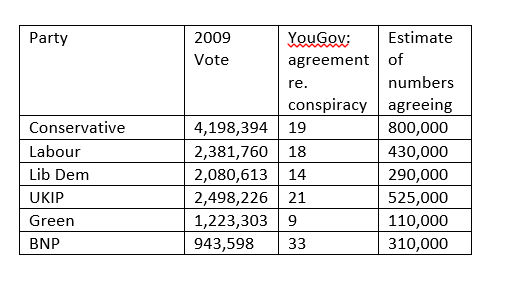

Over the last few weeks there has been much rumbling about antisemitism in the Labour party, with the story of an activist suspended, reinstated and suspended again, and a continuing inquiry into Labour student societies. This, of course, is an issue that has been around for a long time – ‘antisemitism of the (far)-left’ – which has come to attention due to the potential leftwards shift of Labour’s membership, and questions about Corbyn’s leadership. I’m not addressing this here, but I think Rachel Shabi in the Independent and Owen Jones in the Guardian are worth a look, as well as Jonathan Freedland and Nick Cohen. It is important to note that left-wing racisms (including antisemitism) will have a different source and texture to right-wing racisms, due to different relationships to anti-imperialism/imperialism, capitalism and so on. That said, many if not most people will not have a thought through ideology: gut instincts based on more general cultural norms are more of a driving force for people. Indeed, given that racisms are part of society, and political parties are made up of people, it would be surprising if we didn’t find antisemitism or any other racism in a particular social grouping. I’ve made this argument about football before, and I do like the question Ted Croker put to Margaret Thatcher, in response to the question of what football was doing to keep its hooligans out of society… "what is society doing to keep its hooligans out of football?" (The Guardian). Political parties are not immune to societal racism. Along these lines, then, if one wanted to know whether a political party or any other social category has an unusually high problem with a racism within its ranks (given that all will have some), it is not enough to point to an instance or two. Instead, we need to ask whether the prevalence is any higher than society at large. Unfortunately such figures aren’t produced very often, for one reason or another. When they are, it is often part of the political dynamic of trying to cast a group in a bad light. When the BNP looked like they were going to gain some success in the 2009 European elections much was made of how much of their support was drawn from people with problematic attitudes. So the anti-fascist campaigning magazine Searchlight said ‘amazingly one third of BNP voters agreed or partially agreed’ that there is ‘a major international conspiracy led by Jews and Communists to undermine traditional Christian values’. However, no media reported on the wider findings in which a large number of the voters of all parties agreed. Given that the number of voters for the main parties are larger, most of those agreeing were Conservative and Labour voters. Taking the YouGov poll and combining it with the numbers who did vote for these parties, it suggests the following: What this tells us is that there should be about 310,000 BNP voters who believe (to some extent) in ‘a major international conspiracy led by Jews and Communists to undermine traditional Christian values’ but about 1.5 million mainstream voters who will answer the same way.

Similarly, Tim Bale’s more recent research found that ‘some 13% of UKIP voters said they would be less likely to vote for a party with a Jewish leader… only 7% of Conservative voters said the same… for the Liberal Democrat voters, the figure stood at 6% and for Labour 4%’ (The Conversation). To me this is not surprising: preferring ‘people like us’ is normal for the middle-class and middle-aged, and so there will be more less-ideological antisemitism wherever we find people like this. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine that any particular party doesn’t have members with more ideologically developed antisemitism. The Green Party has had its own issues in this area (see here) as has the Conservative party (see here and here). In my own research, I was once present at a meeting in which a serving and senior Conservative councillor argued that all debate on Israel/Palestine is impossible due to all the main parties being funded by a Jewish lobby. The bigger sociological question, though, is how this is all connected, in terms of how ideologies of racisms are contoured in society, how ideologies (common-sense and developed) are understood and delineated into acceptable and unacceptable, and how the understanding of social groups and institutions become part of how racisms are understood and studied. First, the implicit association test shows that everyone, or almost everyone, is prejudiced to some degree, but we know that most people’s racisms do not lead them to extremism or violence. We should then ask how the everyday casual racism of the average person is connected to more problematic forms both in terms of ideology and transport through society. Second, society or parts of society judge racisms to have varying degrees of harm, and this is to some degree independent of any objective measure (e.g. whether violent or not, whether leading to discrimination or not). Some racisms are subject to little censure, some are beyond the pale, and such judgements arise out of the socio-political dynamic of national ideology and common sense and a range of oppositional forces. Third, understandings of social groups (‘race’, religion, class and so on) are often the basis for how we study and interpret racisms, including ideas about uncouthness and sophistication, workplace cultures and so on. So an ideal sociological research programme on racisms would be interested in polite middle-class or dinner party racisms (including antisemitism and Islamophobia), as well as the less polite, especially where such people hold political, economic and cultural power.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2022

Categories |