|

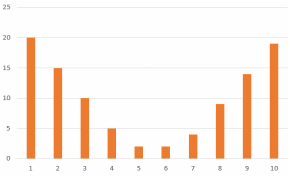

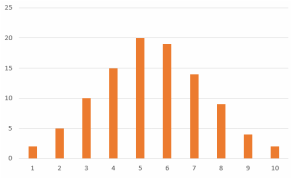

Sajid Javid’s comment on Brexit last week ought to be required reading for all those who want to perpetuate the idea that Britain is ‘deeply divided’. He implied that his decision on the referendum was a close call, where he was conflicted between his heart and head, and where he made a decision one way, ‘on balance’. My suspicion is that he is not the only one, and that there are many more people in the UK who were and are neither fully in support of the EU, nor fully opposed. Divided could mean more than one thing, of course. If it merely means that there is a difference of opinion – that just over half of voters voted Leave and just under half voted Remain – then this is trivial and always the case, everywhere. After all, in each election a certain percentage voted for the winning party and another percentage did not. The use of this term implies something more. Either the social base of the vote is highly skewed so that those on one side of the divide will not know and/or the strength of opinion is such that it will be difficult to create a compromise that will appeal to a large majority. This is what political scientists call a ‘cleavage’. The belief that the social base is highly skewed is inherent in the arguments that the ‘left behind’ drove Brexit. While there is some truth in this, it is not the whole story and the skew is not enough to justify a ‘divided Britain’. Yes, it is true that a higher percentage of poorer people voted Leave than the proportion of richer people. However, as an absolute number, more middle class people voted leave than working class (see Danny Dorling’s work on this). It is also true that younger people were more likely to vote Remain than those older, and Londoners were more likely to vote Remain than those up north and in the home counties. But none of these skews were as high as the class based vote skew of 1966, when 69% of those in classes IV and V (partly skilled/ unskilled manual workers) voted Labour and 75% of those in class I (higher managerial and professional) voted Conservative. If Britain is divided, it was more divided back then. What really drove Brexit was a coalition of rich and poor, with a mix of reasons for voting Leave. Indeed, it is this mix of reasons and the resultant attitude to Britain’s membership of the EU that I think is far more interesting. Sajid Javid’s ‘heart and head’ seems to point to the trade-off between issues of sovereignty and control (the heart) and issues of economy and prosperity (stereotyped as the rational, so the head). Others may have other reasons that have to be balanced, including the argument that the EU is too pro-business and TTIP, or that a co-operative union helps avoid another European war, or arguments for and against migration and freedom of movement. Whatever the viewpoint or political worldview, I doubt there are many that see the EU as an unalloyed force for the good, or as the fount of all evil. Nor will that many people have only one dimension of preference, even if we can say that one dimension is the most important. Unfortunately, the political debate has been played out as though the default positions are polarised, and that only one dimension (immigration) is important. This matters. A referendum, like an election, requires people to boil down their preferences to one side of a line or the other. As such, we just do not know the strength of feeling of any particular vote. We could assess attitudes to ‘Britain being in the EU’ on a Lickert scale of say 1-10, with 1 being the strongest leave and 10 being the strongest remain. It is entirely possible that most people are clustered at 1 to 3 and 8-10, in a U shape, with few in the middle. Or the spread could be a bell curve, with most people in the middle and few at the extremes. The former is a divided nation, with attitudes polarised, and some form of compromise that most can live with is unlikely: a lot want hard Brexit, and a lot want full integration and whatever the outcome, about half of people will be deeply unhappy. The latter is not a divided nation, with attitudes clustered around the middle. In this situation, some form of change (soft Brexit, reform to Britain’s relationship with the EU) will satisfy a reasonable proportion of people and will not be opposed by even more, with only a small minority of people at the edges being unhappy at the outcome. The most important thing to note, however, is that this is always the case. That’s the nature of democracy: whether in coalition or as a ruling party, governments tend to do compromise as they are in the business of taking enough people with them to avoid conflict and the possibility of losing power.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2022

Categories |