|

Whether ‘reciprocal radicalisation’, ‘cumulative extremism’ or ‘interactive escalation’, a key question for policy makers as well as researchers is how new people get drawn into conflict. After all, at any one moment the number of British citizens or residents actively involved in extremism (whether violent or non-violent) is a miniscule proportion of wider society. In my own research, where I spent time doing ethnographic and interview research with radical Islamist (mostly al-Muhajiroun associated) and far-right (BNP, EDL, and others), there were around 20 or so committed activists in total, with a few dozen other less so, in a city of a quarter of a million. I used to think that the solution to the choreographed confrontations between the EDL and al-Muhajiroun, was to send the small number of people involved to an island to fight it out. This would leave the rest of us, probably 99.9% of the population, to get on with life, rubbing together in a messy multiculturalism. However, at face value it appears that theirconflict is connected in some way to wider social conflict: the question is how? I have come to an answer to this by thinking about radicalisation journeys, and particularly by thinking about what I and Phil Edwards have described as ‘microradicalisations’. This terminology is used because state and society (and, of course, research) is not only concerned with the change in behaviour from being an ‘upstanding’, ‘normal’ and entirely peaceable member of society to a lawbreaking ‘extremist’, as though these were two mutually exclusive and homogenous categories. As the term escalation implies, the processes we are examining include small conflicts getting bigger and as such includes activity that is not subject to legal constraint or response. In much the same way, two children bickering or adults arguing in the street is not illegal, but it could escalate into something that is. Furthermore, given the role of state and society in reacting against extremism whether through action or rhetoric, where this takes the form of fear, anger and a need to ‘do something’, then this is itself an escalation of conflict, another microradicalisation. This is not to say that such escalations are inevitable. Most low-level conflicts can stay small or blow over, with escalation and de-escalation continuing as an iterative process. As Marc Sageman argues, “do not overreact… [many will] move on with their lives”: even in the world of the far-right and radical Islamism, it is possible to ‘flirt’ with ideas and behaviours that the rest of us find distasteful and perhaps dangerous, and then leave them behind. Furthermore, we can also include here a far wider range of conflict behaviours, including those based in gangs and territories, anti-authority sentiment, and even generational and other family disputes. Here, then, I argue that the overbearing nature of a narrative that connects small scale extremisms, travelling jihadis, a ‘clash of civilisations’ and communal division, means that every instance of any conflict can be interpreted as contributing to this particular conflict. This is ever more the case when individuals’ beliefs and activities are explained in this common sense narrative as being attributable to community membership. Thus, in this model, one person is homophobic because they are Muslim, another is racist because they are white and working class, whereas the middle-class racist or homophobe is this way for their own individual reasons. Further, society’s response, including academic analysis, can support this narrative and generate more conflict. I interviewed K in 2010, after he had come to the attention of the police for radical Islamist activism, but before terrorist activity for which he received a lengthy prison sentence. He told me he hadn’t been particularly religious as a child, and it did not sound like his family was either. However, he was a naughty kid, often in trouble with teachers at the comprehensive that was very working class, with mainly white British and a sizable minority of pupils with Asian (mainly Pakistani) backgrounds. I saw the beginnings of his Islamist identity in a blow-up with teachers, after he told me: “I was fasting that day. That is the only day I fast. Like I wasn‘t practicing but I, I really wanted to fast this day. I woke up in the morning to fast and I said I‘m never, not going to break my fast. No. I said to my teacher no I said to her I‘m fasting I don‘t want to… We were making cakes or something. She said you have to make it. I said I don‘t want to you know what I mean bro? I don‘t want to. Because I‘m fasting. She said go to your own country and fast. Go there and do the fasting. I got angry. I got angry. I was an angry kid them days. I started throwing stuff. I got very, very angry. Then the head teacher came and like the senior head came in and they all… I said she said go to my own country. And why didn‘t they say nothing to her because she was an authority.” Here, K’s microradicalisation is not informed by a radical Islamist ideology, but is rooted in a fairly unformed Islamic identity mixed with the anti-school and anti-authority sentiment common in working-class boys, echoing Paul Willis’ Learning to Labour. Teachers, having a similarly unformed Islamophobia or national chauvinism responded in a way that made the Islam/Britain relationship into a dichotomy. In each direction, then, behaviour and attitudes that are not necessarily components of extremism or communal conflict are interpreted as though they were. England flags could be a sign of the world cup, or because the residents inside want immigrants to go home. Hijab could be a fashion statement, or a statement of religious superiority. As the dominant explanation of extremisms is that they are outgrowths of particular ethno-religious, or other ‘communities’ – a problematic term that could mean anything from the set of people sharing one attribute, to a set of people sharing everything – then small and unproblematic cultural forms are then interpreted as the pre-cursors to the most serious problems. Our current obsession with risk (reduction) makes this ever more important. Even young Asian boys playing football in a war memorial park can be interpreted as part of the conflict, even if they themselves do not see it that way, as they are seen as exemplars of a culture (Islam) that does not respect another (Britishness). Thus, those that are genuinely part of extremist subcultures are then seen as a part of a threat that is imagined as those that belong to those ‘communities’ they are stereotyped as being rooted in. The threat is therefore magnified from a few thousand to few million. This, I argue, is how the accumulation of conflict operates, with the white noise of a potentially infinite number of microradicalisations, some connected and many not, being crystallised into communal conflict, as they are all examined through the lens of a ‘clash of civilisations’, or its local equivalent in ‘community cohesion’. Originally published as part of CREST, Lancaster's 'Reciprocal Radicalisation' themed report, with contributions from me, Joel Busher and Graham Macklin, Tahir Abbas, Sean Arbuthnot, Paul Jackson and Samantha McGarry, and pulled together nicely by Ben Lee, Kim Knott and Simon Copeland.

https://www.radicalisationresearch.org/debate/briefings-reciprocal-radicalisation/ https://crestresearch.ac.uk/resources/reciprocal-radicalisation

0 Comments

Brunswick Street, Hanley (Mikey/Flickr CC BY 2.0). The building to the right was for a long time home to Mike Lloyd Music, where I spent much of my time and money. In an idle moment at work the other day, I picked up a recent issue of a high-ranking journal. I knew a few of the contributors, so had a read, and found my own words reproduced. I’d been a research participant a few years ago, interviewed in the home, and long ago lost touch with the researcher. Now the article had finally been published, and I found that it misrepresented me in fairly serious ways, and if it hadn’t been anonymous I’d have been pretty cross. More important, though, this raises questions about how sociological research makes claims to knowledge, how participants’ words are interpreted by researchers, and how it is difficult to understand someone or something without a huge amount of contextual knowledge, something we can’t have now because we don’t have the time.

I am not going to quote from the article, or even provide a reference. First, this is in order to preserve the anonymity of participants. Second, because it would not be fair to the researcher, who only has the spoken words and his own theory of the world to understand it. As you’d expect, the work was on the things I have an interest in – why else get involved? – and covered aspects of locality, class and leisure. The misrepresentations were related to class and local knowledge. The first came in an argument about class that assumed I was a particular kind of middle-class person, and so disconnected from other currents of knowledge and culture. The second was related, in that it was arguing that I’d made a claim of knowledge about the local area that was not true. Because it’s about Stoke, this latter part is what felt most like a personal affront. Indeed, this second argument seemed to have come from a basic misunderstanding of what I was talking about, which can be attributed to the researcher’s shorter-term engagement with the city than my own. So while I talked of the decline of a particular street in town as being a recent phenomenon, the researcher felt I was wrong because to him it had always been full of empty shops.* However, my use of the term recent meant the last two decades, whereas it seems he thought I meant in the last few years. The first argument is much more deep, however, and comes from what is not said as well as what is said. As I’ve pointed out recently, I’m now firmly middle class but certainly wasn’t when I grew up in one of the most deprived neighbourhoods in a very deprived city. So while on the one hand I know have taken on some very middle-class ways, on the other I remain connected – in numerous ways – to the working-class environment I grew up in. Depending on the audience, I have often presented very different faces and in some circumstances I would not talk about any of this. I don’t remember the interview, but I doubt I will have talked about my upbringing or family. What I said in the interview was written up as a middle-class snob, being disparaging of a local working-class culture that I know nothing of, the very stereotype of the privileged not understanding what it is like not to be privileged. When I showed this to friends and family, the response was ‘that doesn’t sound like you at all’. I presume the quotes attributed to me are accurate reflections of the words, although I know from experience that small errors made by transcribers (especially missing words) can make a great difference to the meaning. Even if accurate, though, the quotes are partial. An assessment made on other quotes from the interview would be different. On another day, I might have formulated my thoughts into words differently. From some perspectives this does not matter. If the words were said they were said, and they are part of, and evidence for the way that ‘we’ represent what is going on ‘out there’. So whether the words express my beliefs or not, they can be seen as connected to a societal discourse on class. This, however, makes sociology merely journalism with theory. The research that is funded, the questions that are asked, and the use of parts of the interview transcript are chosen because they fit with sociology’s (and at least part of wider society’s) theories about the way the world works. I’m certain I’m also guilty of this practice too. The problem is, another theory could just as easily be supported by other words, interviews, or individuals. Just as computer algorithms stand accused of taking a problematic social reality and making it solid, so sociology runs the risk of reinforcing its own theories by only using data that supports them. Despite claims of radicalism, some sociology is then deeply conservative as the writing is more reflective of researcher bias than the mess of social reality, and this bias reflects the traditions and backgrounds of the discipline and researchers. So what should be done? There is no view from nowhere, and my biases are surely similar. A plurality of voices may help, as would openness in methods, data and analysis. Mostly, though, we need to pay more attention to context and process, not imagining each individual person, interview or statement as a ‘data point’ (unless under experimental conditions). This, though, would require different methods, somehow holistically seeing the wider picture. Sometimes I think historians have got it right – with a method of read, think, talk, repeat. *Example is changed to preserve anonymity Recent talk of extremism and universities, the Prevent duty and so on reminded me of something I wrote back in April 2001. It feels odd now, especially given that some of the explanation of the online was done because it was all so new (imagine that!).... this first appeared in a Goldsmiths publication:

In the week of the first UK Holocaust Memorial Day I watched as a Goldsmiths’ student attempted to purchase a Hitler Youth Armband. Regrettably I did not attempt to talk to her and so at this point I can only guess her motives. I cannot also be fully sure of the reasons behind my own actions and inaction. The situation throws up questions of ethics, authority and political action. However, without talking to the student these questions cannot be answered. I’m not a particularly nosy person. When the student sat next to me in the first floor computer room to do her email I noticed her red hair, boots and fishnet tights my only thought was that there are always new punks to replace the retirees… much the same as the goths. I took more notice of her when she was browsing the online catalogue of Data records, a Coventry record shop specialising in old and new punk. Working in a record shop myself and for a long time being responsible for this shops online catalogue I am always curious about competitors. So as I thought about planning my essay I took occasional glances at the next screen. The student’s record browsing told me that her main interest was Skinhead and Oi!. Although the skinhead movement is widely perceived as being white, working class and racist this image has been contested since its beginnings. Many bands resent being categorised as racist and describe themselves as ‘anti-racist Oi!’. Apart from the notorious Skrewdriver the overt stance of most bands is either anti-racist or ambiguous. In addition, this straight translation of political affiliation from band to fan is problematic even if one is in the audience. This is also more often the case with fandom at a geographical or temporal distance. As with the current goths, many punks in London are from other countries in Europe and so do not have the same background influences as the stereotypical white, English, working class punk or skin. It was what happened next that surprised me. The student began browsing listings of Nazi memorabilia on Ebay (www. ebay.com), an online auctioneer. She spent between thirty minutes and an hour browsing through photographs and descriptions of medals, armbands and signed photographs amongst other souvenirs of the Third Reich. At first it looked like youthful curiosity but all the way through the browsing the student was using a calculator to convert currency (into UK pounds or her ‘home’ country’s currency?). And then it happened. She saw a Hitler Youth Armband at the right price and made a bid of 15.50 for it. I have tried to think of explanations for this behaviour. Research? But why actually buy an item. Fashion? Medals maybe, but in what circumstances would you wear the armband? And it’s hard to see how signed photos of prominent Nazis could be a fashion accessory. As a prop for a play? She would have been looking for a specific item and not comparing prices of medals AND armbands. As part of a historical collection? Surely she would have looked at memorabilia from other wars. It was the requirement for authenticity that really closes off these possibilities. For fashion purposes the painting of a swastika onto a ripped T-shirt would be enough. It is hard to imagine a situation in which this level of authenticity would be a requirement. A trip to an army and navy store would usually suffice. At this point I felt a need to speak to her. But I also knew that in the library I do not have the authority to tell others what they can or cannot do. I also knew that as soon as she knew I was watching her behaviour would change. A warning would also enable her to find an explanation for her potential purchase. However, I needed to know that I could find out who this student was before leaving the library. In the end I decided to speak to whoever was manning the computer helpdesk. I was informed that there is an ethical policy regarding the use of Goldsmiths’ computers. He was sure that pornography was banned but did not know whether the purchasing of Nazi memorabilia was permitted (the purchasing of Nazi memorabilia is legal in the UK but banned in France, Germany, Austria and Italy). He also assured me that the records of who is logged on where and any network traffic is stored. I knew at this point that any conversation or confrontation could wait. I left the library a little confused. I felt that I needed to talk to someone and ask advice about what to do next. I also felt disappointed that I did not take the opportunity to talk to her and would probably not follow it up with more research. In some ways that is why this is being written. As it is now in the open it compels me to finish the story, to find the student and discover her motives. Technical Note: When using the Internet your activities are recorded in many places. Your computer keeps a copy of the material (a cache) in order that it does not need to be retrieved again if it has not changed. Your web server at your Internet Service Provider (e.g. Goldsmiths or Freeserve) can log any page requests and may also keep a cache of data to speed up access to commonly requested pages. In addition the server that hosts the website keeps records of which computers have requested the pages. If I was browsing the BNP website from the Goldsmiths’ library the creator of the website would have a record of goldsmiths.ac.uk requesting pages. In commercial circles this is used to see how popular the site is and from where people are looking. Of course the BNP webmaster has no way of telling whether the user was a supporter, an enemy or just indifferent but even by browsing the site you inform him that he has had an influence. I enjoyed Catriona Paisey and Betty Wu's article in the Conversation, which argues that the gender pay gap is not the only discriminatory inequality that government should look to examine and perhaps address. They are right that unequal distributions of goods that correlate to attributes that should not affect worth (e.g. gender, ethnicity, originating social class) are evidence of some form of problem. It seems likely that, for whatever reasons, the economy does give some types of people better chances than others. That said, these approaches rarely open the can of worms which is what we think about inequality in general. Much of the politics in this area seems to be based on a form of luck egalitarianism. That is, because the individual can't be held responsible for whether they were born male or female, white or brown, and so on, then they shouldn't get any detriment. This is opposed to 'desert', where society accepts that someone who works hard should be rewarded more than someone who is lazy. So, the argument goes, we should try to do something to equalise distributions based on the former, but not on the latter. However, what do we count as luck? Is being born clever luck? Is having parents who read to you at night luck? Is choosing an interest, aged 10, that happens to coincide with what the economy wants 20 years later luck? In the end, almost everything might have an element of luck. Hence my response to the article, below. I don't think we can iron out all effects of luck as it is everywhere. Therefore, it makes more sense to address inequality more generally, which will have the effect of reducing all the gaps we are currently concerned about, as well as ones we ought be concerned about... The other problem with such analysis is that in analysing a gap between the average incomes of two definable groups, we then stop being interested in the incomes distributions within these groups or, by extension, within the group of ‘all humans’. Indeed, such gaps appear in a myriad of ways. Average income is lower for short men, higher for women considered good looking, lower with increasing distance from capital cities and, of course, lower in the global South. Average income is higher for the better educated, lower for the young, and so on. By looking at averages, we would find the gap changes by the substitution of as few as one person. On a global scale, if the 8 richest men were actually women, then the global gender pay gap would reverse as these 8 would have the income of 50% of the world population. In a company, the pay gap would disappear if one man and one woman at the top earned millions, and the rest earned an equal pittance. Would it really create more justice if a few women at the top meant that an average pay gap did not exist, even though the women at the bottom could still be earning less than the lowest paid man? There is plenty of political philosophy work that addresses these issues, asking: how much luck or background should impact on livelihood and which reasons should be allowed to be relevant to livelihood; whether policy should prioritise raising the quality of life at the bottom or attempt to promote equality; and how equality of opportunity differs from equality and so on. I recommend starting with Anne Philips’ article from 2006 (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2006.00241.x/full) in which she argues that: ‘Majority opinion currently favours something more than the minimal—anti-discrimination—interpretation of equality of opportunity, and looks to a more substantive neutralising of the effects of social background. Yet no government is going to introduce measures that would genuinely neutralise these effects… Equalising opportunities means equalising our chances of the good things in life, but almost by definition, leaves untouched the distribution of rewards between ‘good’ and ‘bad’… They therefore leave untouched the really big questions about inequality.’ While all the gaps between groups described here are problematic, they are all far smaller than the gap between the average of the bottom 50% and the average of the top 50%, whether assessed globally, nationally or, I would assume, within most organisations. And the great thing is, dramatically reducing overall inequality would reduce the gaps between groups, whereas the converse would not be true (see John Hills et al. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/28344/1/CASEreport60.pdf). Picture: Cynthia/ Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

I love analysing social science statistics, especially when they’ve been in the hands of PR professionals and journalists. I think it’s probably because errors are easily disputed and easily traceable, so we can see how social knowledge is created and transmitted: tracking back sources is usually easier as one can search for specific ‘facts’, and where those ‘facts’ feel wrong one can search out the original data. Here I’ll discuss two of this weeks stories, one on burglary and one on university entrance.

The ‘burglary’ story caught my eye because the hotspots seemed unlikely (Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Blackheath) and there seemed to be some slippage in what the story was about. The story is originally from moneysupermarket.com(so it’s a PR story) who analysed their insurance inquiries. So the first important observation is that the data is from a) people using the internet, to b) renew their insurance, and c) doing some shopping around. This is a biased sample in lots of ways: obviously they are people who buy online and have insurance (around 10% of people aren’t covered, presumably the poorest). That they are shopping around suggests that they have made a claim recently too. It’s not hard to imagine that this biases the sample towards 25-34 year old professionals. Furthermore, the original press release gives away the slippage. Although it has ‘home theft hotspot’ in the title, and spokesperson quotes like ”Home is where the heart is and there’s no denying that having it burgled is an emotional and frightening experience”, the data refers to ‘claim[s] for theft on home insurance’. So this includes muggings, thefts from the beach, bikes being stolen, lost wallets on the bus and so on. Again, this is probably biased to young professionals: the kind of people who get their phones nicked in the pub, or have their bike nicked from outside. So to education. ‘Just 1% of poorest students go to Oxbridge’ cries the Guardian. ‘In contrast, 10,827 students attending Liverpool John Moores University and the University of East London claimed a full bursary – 4.7% of the total for the whole country’ This is statistical nonsense. Without knowing how many students in total go to each university we can’t know if these figures are better or worse than average, or bang on. Perhaps 10% of all students go to Liverpool John Moores or UEL, so they aren’t attracting as many poor students as they should. We also don’t know if there are other of the poorest students who are attending and not counted as they get other forms of support or none at all, but I’ll let that go. The original report has the more important figure, ‘the proportion of full fee-paying students this number [those receiving bursaries in the lowest income group] represents’. This in itself is problematic as bursaries are only for UK students, and I don’t know if the ‘full fee-paying students’ include EU and overseas students: I suspect not, but if so then those with more non-UK students will have a lower percentage. Anyhow, the figure for Cambridge of full-bursary over students is 11.1%. This is low, but some are lower: Grennwich – 9.1%, Guildhall – 11%, Leeds Met 0.4% (very strange, I need to look into this). UEL is high at 61% but LJM isn’t particularly high… it’s just a big university. Railway Suicides

As a railway commuter, I have experienced multiple delays due to suicides, and enough to get some sense of their volume and patterns. The one time I was on the train that hit the person, there was an amazing flourishing of a sense of community, with people hugging the driver and conductor when we got off at Manchester Piccadilly. I talked to the conductor a little, while we were waiting, with discussion of the time patterns (Mondays, the week after Valentine’s day, the end of January) and the potential causes for this, which include the arrival of bank statements and credit card bills, broken relationships, jobs and so on. While thinking about this, I did hunt out some statistics, only to find more of the Guardian’s failures to really grapple with numerical data. A datablog on railway suicide has some representations of data with arguments about what is going on, almost all of them wrong. The first is a chart showing an increase in railway suicides over a 10-year period, alongside data on passenger journeys. I’m not even sure any increase isn’t just random variation: because the numbers are so small, what looks like a big percentage change is actually what we’d expect annual variation to look like. Saying that there’s been a 17% jump from 2010 to 2011 ignores the fall of a similar size from 2009 to 2010. And I’m not sure what the passenger numbers have to do with suicides: people of all sorts can go to a station or more usually a bend where the driver won’t see them to commit suicide, it’s not just a subset of passengers. The data does show ‘Fewer suicides on the underground’, and this is argued to be ‘more indicative of lower passenger numbers than station safety’. However, passenger numbers on the underground are at the same order of magnitude as on the national rail (1.4bn v 1.6bn) so this would not explain suicide on the tube being a tenth of that on overground rail. Again, I’m not sure what passenger numbers have to do with it: suicides come from the population of humans, not from the population of train commuters or tube riders (although there could be a correlation due to confounding variables). More likely is the design of the tube system. On the national rail system, it is possible to climb a fence and get onto the track, somewhere where a train cannot stop, or to step off the end of a platform where a train is passing through. All tube trains stop at all stations, and most of the time we can’t get to the track in between stations, so attempting to commit suicide on the tube is far more difficult. The final chart titled ‘One of the highest rates in Europe’ does not show this at all. Yes, we are near the top of the chart, with more railway suicides than all EU nations bar Germany and France. But this is because we are one of the most populous nations. ‘The UK's rail network accounted for around 7% of all suicides that took place on EU rail’ but this needs to be put into the context of having just under 9% of the EU population. A rate needs to be worked out as suicides per population. We’re mid-table here, with the Catholic countries lower than us, but many others higher. I have long considered writing some autobiographical notes on social mobility, as my own path and position is relatively unusual and demonstrates some seldom made points on gender, the multi-factoral nature of the process, and generational effects. However, this has been prompted by a holiday in Italy, in which it seems I have definitely become middle class, a conversation there with a Somalia-born British journalist (Ismail Einashe), and then finding the BBC radio documentary on this topic by Hashi Mohamed, who coincidentally is another Somalia-rooted Londoner who has made it into a very middle-class profession.

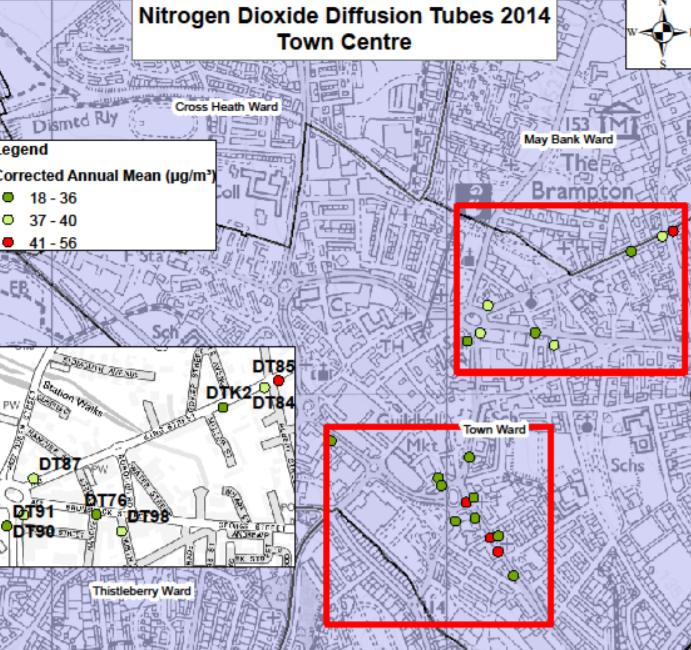

Even on the journey to Italy, I had been thinking about how this was a very middle-class trip. It wasn’t that I was flying Business class, or even with a non-budget airline, but what I was to do once I was there. Not only was I going to be in Naples, with the obligatory visits to the archaeological museum, Pompeii and Herculaneum, and which of course were great: I was also dropping into an academic conference and then hiring a car to get to small town where I could meet a friend who grew up there. Thus, this holiday was also generating the cultural and social capital that we know helps ‘middle class kids get middle class jobs’. I even got to chat to a prominent British sociologist who happened to be at the conference, and who has edited two books on migration with people I know from my time in London. I don’t think this is the end of any journey, but I started life very working class and this change has been a gradual accretion of various attributes. I was talking to Ismail about this, and he mentioned his piece on Britishness for the Guardian, with its focus on belonging and second-class citizenship, the latter being a trope I’ve used in academic work in the past. Indeed, in other work I have written about the process of becoming British that does take in more than the moment of citizenship. What caught my eye in this, though, was the mention of the passport as the end of the process and his recollections of schooldays: As the end of term approached, my classmates would ask where I was going on holiday. I would tell them, “Nowhere”, adding, “I don’t have a passport” At sixth form, doing a History A-level, and armed with citizenship and so passport, he was then able to go on the school trip to Versailles. This, I replied to Ismail, made him a few years younger than me when I got my passport and first went out of the UK. So why was I 20 when I got my first passport? I had the right status as a citizen, but in my family and wider circle there was no history of going abroad: I didn’t think it was something one did, I hadn’t the confidence, I didn’t know how to. This is another attribute that can be a marker of class: like the kids I remember seeing in a documentary about Newcastle-upon-Tyne, I’d barely been out of Stoke-on-Trent for more than a day or so in my life up to the age of 17, other than for Stoke City away games, and had never been to London. The documentary by Hashi Mohamed, now a barrister, mentioned other things, including experience of enjoying and attending classical music and sport events, drinking fine wine and more, that are part of how people ‘fit in’ and so reproduce the same types of people. He also mentioned how particular opportunities for work experience would be available for the children of barristers’ friends. I recommend this documentary as an introduction to the ‘unwritten rules you must learn to get a top job’, but with the caveat that this is true of far more opportunities, with the ‘top jobs’ being some of the most desirable. Me, I spent most of my childhood in a street found to be in the top 1/3 of 1% in the index of multiple deprivation (i.e. 299/300 other areas are less deprived). I’m the only person in my family not to leave school at 16, and all my grandparents and both parents worked in the pottery industry. I also had my education disrupted by family breakup, and was eventually in a household that on today’s standards would be a Troubled Family due to crime, long-term ‘out of work benefits’ and more. I’ve seen alcoholism and violence at first hand. Just as important, though, was the fact that our social networks did not include anyone outside Stoke, and I knew no one that had been away to university, nor anyone who had a job that was not ‘skilled manual’ (except for one I’ll come on to). I didn’t know anything of classical music, or great literature. I didn’t know of the unwritten rules, or even when they might come into play. Avoiding ‘certain fates’ is not just about talent and hard work. Ismail’s turning point was the move to a high performing sixth form, with a diverse range of students. Hashi Mohamed’s turning points came courtesy of Newsnight and a letter asking for work experience, and then a subsequent personal introduction to someone who could help arrange the pupillage. My turning points came both earlier and later, but also involved my mum, who’s a great example of how social mobility isn’t just about improving education and getting a middle-class job. Furthermore, this complicates my story, because the disadvantages described above were coterminous with a couple of serious advantages. The headline complication is that, while my childhood home and where my mum still lives, is one of the most deprived neighbourhoods in the land, when she moved there my mum had just gained a PhD in mathematics. So, yes, my mum grew up in a council house, with parents who both worked in and were killed by the pottery industry, and she did work in the pots too. She got into a grammar school at 11, left at 16 and worked in industry, married, had kids and divorced. But while me and my siblings were small, she did a maths degree with the Open University, and then the doctorate at Keele. After divorce, she became a maths teacher at an ex-grammar that had changed to fee paying, but this was after I’d passed the 11-plus and been offered a place at the same school under the 1980s ‘assisted places scheme’, which enabled kids with poor parents to get fees paid by the government. So what I did gain was educational capital of straight As in science/ maths A-levels and then a Cambridge degree in Natural Sciences, and this paralleled my mum’s educational capital. However, neither of us had the kinds of social or cultural capital, or the being comfortable in middle-class environs, that would often go along with this. My mum still lives on a council estate, just a mile or so from the one she grew up on. By some measures, she has not been socially mobile at all, despite the PhD and teaching job. Perhaps it was a gender issue for a particular generation, certainly a parent/ family issue, but the moving out and moving on just didn’t happen. On the other hand, I stayed at school post-16 and went away to university at 18. At that point I didn’t have much of the transferable cultural and social capital, being still a working class kid into house music and football, and knowing little of the world. But I’ve been able to build on that, and much of it because of the need to make new friends when leaving a home town, and the diversity that comes with doing this in Cambridge and then London (itself geographic capital, perhaps). In the end, after not totally fitting in at school, and moving into another world at university, I’ve become comfortable in middle-class worlds. And as a consequence, I’m doing the next stage of the social mobility, where I move in very different circles to the rest of my family and do the omnivorous cultural consumption of the group I’m now in - ‘Established middle class’ - according to the Great British Class Survey. Knowing this, any denial that I’m middle class would be absurd.  While I’m all in favour of cleaner air, and wish I hadn’t got a diesel for a second vehicle, I’m not sure that the Labour party’s claim that ‘nearly 40 million people in the UK are living in areas where illegal levels of air pollution from diesel vehicles risk damaging their health’ (Guardian) is particularly meaningful. This is both on the grounds of how the data they have is constructed, and also on how pollution affects real, mobile human beings. The first part is partially down to this concept of ‘area’. As a counterpoint, I’ve seen it written that ‘99% of the UK meets European air quality standards’, and we know that this is because it is for geographical area as opposed to population. The 1% that does not meet the standard is where lots of people live. However, it seems that the Labour figures are merely a repetition of a parliamentary question from October. This produced a list of ‘Local Authorities with exceedances of NO2 annual mean limit value’ based on a 2015 exercise*. This exercise appears to have itself (at least where I live) on data from 2014, which comes from numerous sensors across the area. However, in the original (LA level) report for my local authority we find that the NO2 average is exceeded at five locations in two smaller geographic areas inside the borough, with six sites in three locations coming close. This is out of 38 monitoring locations across the whole borough. Thus, for each area, the Labour analysis only tells us that at least one location went above the limit, but it could be just one or it could be all of them. I, therefore, count as one of the people living in an ‘area where illegal levels of air pollution from diesel vehicles risk damaging their health’, but I live in a relatively rural location quite a way from the nearest sensor that detected a breach. Indeed, given that sensors are placed next to main roads, and not by a random sample, the numbers of people living within a specified distance of a breach is also a function of the geography of the area. Indeed, what counts for health is not the indicator of the monitoring station, but how much pollution is present in each person’s air. Presumably there is some sort of diffusion gradient for the pollutants, and the breach figure somehow relates to the potential for danger to someone near to it, but also to the danger for everyone else living further away. Indeed, the breach figure for the sensor is 40µg/m3, but research shows that risk comes from breathing in lower concentrations: I guess the assumption is that no one is living on top of the sensor, and that people are living a distance from those highest polluted spots. Better research would assess the level of pollution in people’s homes. There is, of course, some kind of diffusion gradient for the humans too. We don’t sit in our houses breathing the same body of air all the time, but we move about. I spend some time in places much nearer to the monitors with breaches, as that’s where the shops are, but not much. I also go to other cities and travel through more polluted areas. However, the relationship between the population’s exposure to pollution and the exceedance of the annual NO2 average is not clear: if the breach is in the town centre it is shoppers that will experience it, and if the breach is on a dual carriageway then it is drivers. Once again, the connection is down to the spatial configuration of the place. What is likely, however, is a relationship between income/ wealth and pollution, which goes back a very long way. The configurations of some cities came about because of the way the wind blows: the least desirable places to live were those where the factory smoke blew. At that time a big house next to a main road was desirable, however. Now the pollution mainly comes from vehicles, a house next to the main road is far less desirable, and those who can afford it maintain a healthy distance from those sites with bad air. Suffice it to say, I’m not expecting the plan that the government has been forced to publish to clear any of this up. As ever, one set of politicians want the problem to ‘just go away’, ideally for no cost, and the others want to use the data as the stick to beat the former. *We could also ask why NO2 and not particulate pollution has become the focus of the debate. In the borough I discuss PM10 (particulates <=10microns) is measured at only one site, and annual average limits are not exceeded, which I presume gives a different story for politicians and activists. If it’s not measured, it doesn’t exist! Radical, radicalism, radicalisation. Much has been written to define these words, especially since Islamist bombs came to Europe in 2004, but they remain a source of conceptual confusion (Sedgwick, 2010). Donatella della Porta and Gary LaFree described seven different uses of the term radicalisation (2011), all of which include a move to violence. Other definitions do not require any mention of violence, but merely a movement towards extreme views. In this short piece, I wish to redefine radicalisation, but without defining radical, radicalism or extremism.

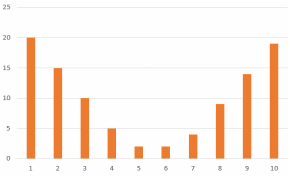

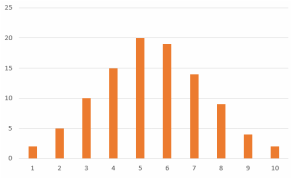

Indeed, I wish to reclaim radicalisation as a word describing a process, precisely because all those end points (radical, extremist and so on) are contested concepts. As pointed out be Schmid, ‘radical’ once described those agitating for democracy against despotism (Schmid, 2013). Definitions of ‘extremism’ that rely on difference from an assumed norm are dependent on the nature of the norm and some sort of ‘relative, evaluative and subjective’ (Mandel, 2009, p. 105) comparison. What the mainstream sees as the problematic end-points differs across time and space. Hence ‘one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter’ if there are differences in ideological norms. What we consider to be violent or unacceptable conflict depends on where we put the limits of acceptable conflict: disagreements here are why we have debate in Western nations about the limits of free speech and what can be prosecuted as terroristic. More importantly, the drawing of a line can reduce the concept of radicalisation to the process of crossing the line. Radicalisation ought to mean the process leading up to the crossing of the boundary, and subsequent processes of escalation. This problem of definition, in essence, is that objects like radical, extremist, violence and terrorist are ones that require bounding – one is either a radical or one is not, an incident is violent or it is not – whereas radicalisation describes a process which does not have a boundary. Given that individuals, groups and societies are not wholly circumscribed by what happens to be the law at a given moment, any line drawn is arbitrary and cannot be the whole story of the longer process. Radicalisation, as a sociological concept, could therefore be much simpler. One such definition could be ‘movement towards conflict’, or as McCauley and Moskolenko put it ‘as changes in beliefs, feelings and behavior in the direction of increased support for a political conflict’ (2010). This, then, is something that is everyday and commonplace, and is something that individuals, groups, governments and societies are undergoing all the time: there is constant movement towards and away from conflict, and this conflict can be legal or illegal, violent or nonviolent. Such a definition implies no moral judgement, and places radicalisation as the process in which politics moves along a scale from total consensus to war. From any particular political/ideological viewpoint, some radicalisation is done in aid of the good, and some furthers the bad. This definition makes radicalisation a process akin to aging, albeit with plenty of potential for reversal. Radicalisation is to radical as aging process is to aged. Just as we can accept that the aging process is something that all life undergoes all the time, but we reserve the term aged for those that have undergone lots of it, so we can reserve the term radical for those at the furthest point in the process. Young people are aging and may or may not become aged (they may not get there). Ordinary people radicalise and deradicalise, and may or may not become radical or extremist. Undergoing the process, defined like this, is not dependent on the crossing of a socially constructed line. Furthermore, this definition is not reliant on the attempts to create solid foundations that are found in definitions of radical or extremist. Unless we assume that the liberal democracy we have now is perfect (can’t be true) or is at least the best we will ever have (can’t be proved), the labelling of something as radical or extreme is contingent, and may be subject to historical change. When distance from the political norm, and the willingness to use violence, are the markers of radical or extremism, then we must include Nelson Mandela and the Suffragettes (but perhaps not suffragists or Martin Luther King). Such examples show that judgements made to which radicalisations are acceptable and unacceptable are inherently political, and attempts to depoliticise the debate are bound to fail. Seen this way, radicalisation is not seen as automatically problematic from some imaginary neutral position, but is deemed problematic from a specific position. It is important to note that the notion of movement towards conflict requires at least one other party: one group needs another to conflict with. Furthermore, there are usually multiple actors in any conflict, and while the state might attempt to draw lines around what is what I call ‘problem radicalisation’, these may not coincide with the lines that others may draw. So while the legal framework may protect free speech, some speech can be seen by others as on a radicalisation spectrum. While freedom of conscience, culture and religion are promoted by liberal democracies, some expressions can be viewed as problematic. Thus from a US perspective, the flying of a flag should raise no alarm bells, and from the perspective of 1950s UK wearing a veil would raise no alarm bells. In contemporary Britain, both can be interpreted as low-level radicalisations that are legal but somehow connected to the more problematic radicalisations of the far-right and radical Islamists, white and Muslim terrorists. Thus what is called ‘reciprocal radicalisation’ can be one set of people’s response to another sets actions, even when those actions are not recognised as problematic by the rest of us. More importantly, given the distribution of power, movements towards conflict made by the state can be felt as a threat, even when not meant to: the banning of demonstrations, or the criminalisation of dissent, is a radicalisation that some will view as problematic. So while this definition of radicalisation – movement towards conflict – is broad, and without a value judgement, the dynamic of radicalisations and the limits set on good or bad radicalisations cannot be approached without political referents. Responding to radicalisation cannot be done with reference to some neutral viewpoint, but is political, as we should assume that at least the extremists disagree on visions of the good society. This was evident to me when interviewing an imam, fed up with the al-Muhajiroun extremists on the street outside his Friday prayers. He wanted them banned, but also for fairness wanted the BNP banned because they were ‘the same’ and because ‘racism is illegal’. This, then, ought to be subject to analysis and debate. For either the BNP and al-Muhajiroun are the same level of threat and should both be banned or both be legal, or they can be shown to be different, and different penalties apply. This debate ought to have been something that all could take part in, and with different positions allowable: otherwise the minor radicalisations are such that ordinary political conversation is replaced by more conflict. This post was written a few months back for a corporate blog, but due to a rebuild of the site it got a bit lost. Now it's a trailer for a forthcoming piece in the Journal for Deradicalisation, written with Phil Edwards at MMU... Sajid Javid’s comment on Brexit last week ought to be required reading for all those who want to perpetuate the idea that Britain is ‘deeply divided’. He implied that his decision on the referendum was a close call, where he was conflicted between his heart and head, and where he made a decision one way, ‘on balance’. My suspicion is that he is not the only one, and that there are many more people in the UK who were and are neither fully in support of the EU, nor fully opposed. Divided could mean more than one thing, of course. If it merely means that there is a difference of opinion – that just over half of voters voted Leave and just under half voted Remain – then this is trivial and always the case, everywhere. After all, in each election a certain percentage voted for the winning party and another percentage did not. The use of this term implies something more. Either the social base of the vote is highly skewed so that those on one side of the divide will not know and/or the strength of opinion is such that it will be difficult to create a compromise that will appeal to a large majority. This is what political scientists call a ‘cleavage’. The belief that the social base is highly skewed is inherent in the arguments that the ‘left behind’ drove Brexit. While there is some truth in this, it is not the whole story and the skew is not enough to justify a ‘divided Britain’. Yes, it is true that a higher percentage of poorer people voted Leave than the proportion of richer people. However, as an absolute number, more middle class people voted leave than working class (see Danny Dorling’s work on this). It is also true that younger people were more likely to vote Remain than those older, and Londoners were more likely to vote Remain than those up north and in the home counties. But none of these skews were as high as the class based vote skew of 1966, when 69% of those in classes IV and V (partly skilled/ unskilled manual workers) voted Labour and 75% of those in class I (higher managerial and professional) voted Conservative. If Britain is divided, it was more divided back then. What really drove Brexit was a coalition of rich and poor, with a mix of reasons for voting Leave. Indeed, it is this mix of reasons and the resultant attitude to Britain’s membership of the EU that I think is far more interesting. Sajid Javid’s ‘heart and head’ seems to point to the trade-off between issues of sovereignty and control (the heart) and issues of economy and prosperity (stereotyped as the rational, so the head). Others may have other reasons that have to be balanced, including the argument that the EU is too pro-business and TTIP, or that a co-operative union helps avoid another European war, or arguments for and against migration and freedom of movement. Whatever the viewpoint or political worldview, I doubt there are many that see the EU as an unalloyed force for the good, or as the fount of all evil. Nor will that many people have only one dimension of preference, even if we can say that one dimension is the most important. Unfortunately, the political debate has been played out as though the default positions are polarised, and that only one dimension (immigration) is important. This matters. A referendum, like an election, requires people to boil down their preferences to one side of a line or the other. As such, we just do not know the strength of feeling of any particular vote. We could assess attitudes to ‘Britain being in the EU’ on a Lickert scale of say 1-10, with 1 being the strongest leave and 10 being the strongest remain. It is entirely possible that most people are clustered at 1 to 3 and 8-10, in a U shape, with few in the middle. Or the spread could be a bell curve, with most people in the middle and few at the extremes. The former is a divided nation, with attitudes polarised, and some form of compromise that most can live with is unlikely: a lot want hard Brexit, and a lot want full integration and whatever the outcome, about half of people will be deeply unhappy. The latter is not a divided nation, with attitudes clustered around the middle. In this situation, some form of change (soft Brexit, reform to Britain’s relationship with the EU) will satisfy a reasonable proportion of people and will not be opposed by even more, with only a small minority of people at the edges being unhappy at the outcome. The most important thing to note, however, is that this is always the case. That’s the nature of democracy: whether in coalition or as a ruling party, governments tend to do compromise as they are in the business of taking enough people with them to avoid conflict and the possibility of losing power.

|

Archives

May 2022

Categories |