We can all be a little radicalised: recognising this will help tackle extremism

The conviction of radical Islamist preacher Anjem Choudary for swearing allegiance to Islamic State shows that those breaking the law by inviting support for a terrorist organisation can and will be prosecuted. But it comes at a time when the British government is still struggling with definitions of extremism and radicalisation, and how to respond to those who don’t break the law. Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights recently flagged up new concerns about the government’s counter-extremism strategy but we have had around a decade of these debates. Back in 2008, in the wake of the London 7/7 bombings, then Labour home secretary Jacqui Smith spoke of “extremist groups who are careful to avoid promoting violence”. The same year, the Department for Communities and Local Government created a list of British values: “human rights, the rule of law, legitimate and accountable government, justice, freedom, tolerance, and opportunity for all”. Vocal or active opposition to what are now known as fundamental British values has since been defined as extremism. This marks out certain attitudes as potentially dangerous, even if they do not incite violence. I say it’s time for a rethink, and that it should be through reclaiming the concept of radicalisation. On a journeyThe government has defined and tackled non-violent or “legal” extremism through a strategy known as Prevent. The Prevent duty requires public authorities to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism, and it also includes the promotion of fundamental British values. Those judged to be at risk of violent radicalisation can be referred to a multi-agency programme called Channel. Such programmes are founded on the idea that radicalisation is a process. This makes sense: people aren’t born terrorists, nor do they wake up one day with a whole new mindset. Radicalisation is something that starts small and can get bigger. But it can also be reversed – and often is; usually not ending in violence or other illegal behaviour. In my own ongoing work, I have examined the radicalisation journeys of both radical Islamist and far-right activists, using the term “micro-radicalisations” for the small parts of this journey. In 2009, in the months before the radical Islamist group led by Choudary called al-Muahjiroun and later Islam4UK was banned as a terrorist group in the UK, I spent nine months of my PhD fieldwork with a local branch of the group. I interviewed all but one of the six key activists, and spent many, many hours sitting with them at street stalls and attending their public meetings. One of the lead activists reflected on his time in secondary school. He had grown up in a Muslim family, but he was not “practising”, and used fasting as a way to wind up the teacher that eventually, he said, resulted in a physical confrontation and the teacher responding with “get back to your own country”. Another participant, a British National Party (BNP) activist interviewed for the same study, told me of feeling envious as the Asian children in his class got extra attention due to language difficulties. Others told me of experiences in their later teens and twenties, where they experienced police racism or conflict between ethnically defined gangs. Anger about one thing led to actions that would then be met with an angry response from others, creating a vicious cycle. Any involvement in a far-right or Islamist group ended up with further conflict with the police, other extremist groups or other young men just wanting to start a confrontation with the group, fuelling more anger. After the ban, some of the al-Muhajiroun interviewees went far enough to end up with terrorism-related convictions.

Accusing everybodyThese earlier micro-radicalisations do not need to be justified by a fully thought out ideology either. The teenager’s fasting was a facet of young male rebellion, tinged with an incipient identity politics. Even in groups such as the BNP, English Defence League and al-Muhajiroun, many people drift away, for all sorts of political and personal reasons. Anger and even angry violence was clearly there in the backgrounds of the mainstream political and community activists I interviewed too. I met people who had been uncontrollable as kids and who felt that their activism as adults was them giving something back to their community. Others had discovered that getting involved in the local Labour party was a better way of getting the kinds of change they wanted to see. All this means that assuming that any particular microradicalisation is a pathway to terrorism will inevitably create many false positives – people who are accused of being dangerous to wider society but, in the end, are not. In fact, restrictions on free speech as a result of the Prevent strategy could affect many more people than those who would have gone on to violence or other law-breaking activities. These actions are the government’s own radicalisation, moving it towards more conflict. The Prevent programme is one-sided and its bias towards Muslims has led to it being described as “an exercise in Islamophobia”. A fairer approachOne alternative would be to take in all kinds of radicalisation – green, to the left and to the right, anarchists and more. We could restrict everyone’s speech and action, because we cannot predict which might be a threat in the future. But this would lead to real authoritarianism and end Britain’s commitment to free speech. My preferred approach would be to accept that all of us radicalise and de-radicalise at times, and that society and the state should not overreact. Where lines are drawn – especially between legal and illegal activities – they need to be set in neutral terms, and with a commitment to free speech and political debate. More important, however, is the need to make lower-level responses to any real or assumed radicalisation universal and positive, regardless of their origins. This should be based in a presumption of good will as opposed to a culture of suspicion. It should include helping people to engage in politics, even if some of their views are contentious, as a better way of resolving differences. We are not faced with a choice between banning some things and encouraging everything else.

Gavin Bailey, Research Associate, Policy Evaluation and Research Unit, Manchester Metropolitan University This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

0 Comments

‘What we’re gonna do here is go back, way back’ (Todd Terry sampling Jimmy Castor) At some point around 1990/1, I began to spend less money on gig tickets and more on club entry. I’d was a buyer of vinyl, an NME reader, and travelled across England for hip hop and indie gigs. I was still rooted in or perhaps stuck on a working-class peripheral estate in Stoke-on-Trent, but I had escape routes. Weekends had always been dull for me as a 16-year-old, either drinking in the Miners’ Welfare Club where my step-father drank – avoiding the bingo and the covers bands – or going to some straight disco for pop hits. The occasional trip to see bands like Public Enemy and Pixies turned into a weekly habit of dancing to house and techno, in Stoke and further afield. By the time I left Stoke at 18 – for what I thought was for good – I was fully embedded in a house/ techno club culture, and stayed with it (in Cambridge and London) for the next decade, doing a bit of DJing, promoting, working in record shops, and a lot of staying up all night. What I didn’t know, at the start, was that Stoke had seen it all before. At some point, when my step-father’s friend Jack heard I was going to all-nighters, he started talking about the Torch, Tunstall and the Northern Soul events of twenty-years before. There, in the working mens’ club, sat a group of working-class men, who had worked in the mine that had closed in the 80s, or been ‘metal bashers’, but had been laid off in their 40s and never worked again, all on the sick. They would casually use racist epithets, but at the same time one of their number was black, and they would be drinking weak beer day after day, night after night, playing dominoes, cribbage and sometimes darts. It’s easy to see this place in one-dimension: they were the ‘left behind’ in 2016 parlance, and fit all the stereotypes of the lack of education, unthinking sexism, racism, homophobia, lacking interest in politics and culture beyond ‘the village’, the semi-derelict mining estate where we lived. However, even some of these people had been players once, before settling down. I’d even fell for these stereotypes myself, to some extent, changing the signs on the way in to Stoke to say ‘culture free zone’, on a visit back from university (where I’d found far more culture): Perhaps some or all of my academic work has been to repent for this. On joining the middle class (however tentatively), I kind of turned my back on the city, never visiting my family, losing touch. It was only after the city’s supposed turn to the far right, when my own estate had a BNP activist as chair of the residents’ association, that I started to go back as a researcher. I spent time there with groups working with refugees and white teenagers who skipped school, and with the far-right and radical Islamist groups that gave the city a bad name. What I’ve tried to do is show how the stereotypes of place, be it ‘white estate’ or ‘Asian streets’, and the association with poverty, backwardness, intolerance, are never the whole story. As I saw in the working men’s club, racism can be in the same body as a welcome to the ethnic other, a memory of flourishing youth culture in the same place as day-in/day-out boredom. Is Stoke a city of no culture, or was it ever? My plan, then, is to revisit this through questions about Northern Soul, techno and rave, Stoke-on-Trent, and Detroit. For a year, the Golden Torch was a key part of the Northern scene, and around two decades later Shelley’s was a key part of the rave scene. Both times, the local authority closed down the venues, although the scene lived on elsewhere. In both, much of the music emanated from black artists in Chicago and Detroit. The first time around a Stoke-based designer took Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ 1968 Black Power salute to create the logo above. The second time around, Staffordshire’s Neil Rushton (and involved both times) solidified a genre with a compilation of Detroit-based tracks under the name Techno: The New Dance Sound of Detroit. Stoke-on-Trent, the BNP’s ‘jewel in the crown’, embraced Afrofuturism, in the sounds of the Belleville three, and then in the British sounds of hardcore and drum ‘n’ bass. Necessarily, this embrace must be seen in the context of industry and later de-industrialisation, and the sound of a city’s machines becoming quieter. The jobs in heavy industry, in Detroit and Stoke-on-Trent, declined from the 70s onwards, and by the late 80s the machines were becoming ever more automated. Derrick May (Mayday) is quoted on the sleevenotes of Techno as saying that ‘black people no longer care if they never work again’, and that was just as true for the middle-aged men in the working men’s club. The few people left in the pottery factories were often reduced to pressing a button. So why this music? The first time is often associated with one form of adolescent escapism, with the optimism of emancipation in soul music and the joy of the dance being in contrast to the drudgery of the factory floor, and the bleakness of the industrial landscape. The second time, however, was an entirely different form of escapism. For Simon Reynold’s it was a nihilistic withdrawal from the de-industrialising city, with few jobs and no alternatives. Techno itself was birthed from a ‘broken promised land’ (Albiez 2005): did we in the UK’s midlands and northern cities hear the music, and know?

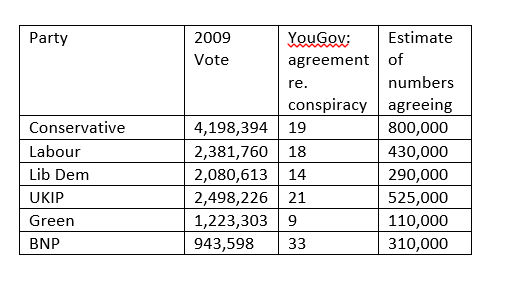

Over the last few weeks there has been much rumbling about antisemitism in the Labour party, with the story of an activist suspended, reinstated and suspended again, and a continuing inquiry into Labour student societies. This, of course, is an issue that has been around for a long time – ‘antisemitism of the (far)-left’ – which has come to attention due to the potential leftwards shift of Labour’s membership, and questions about Corbyn’s leadership. I’m not addressing this here, but I think Rachel Shabi in the Independent and Owen Jones in the Guardian are worth a look, as well as Jonathan Freedland and Nick Cohen. It is important to note that left-wing racisms (including antisemitism) will have a different source and texture to right-wing racisms, due to different relationships to anti-imperialism/imperialism, capitalism and so on. That said, many if not most people will not have a thought through ideology: gut instincts based on more general cultural norms are more of a driving force for people. Indeed, given that racisms are part of society, and political parties are made up of people, it would be surprising if we didn’t find antisemitism or any other racism in a particular social grouping. I’ve made this argument about football before, and I do like the question Ted Croker put to Margaret Thatcher, in response to the question of what football was doing to keep its hooligans out of society… "what is society doing to keep its hooligans out of football?" (The Guardian). Political parties are not immune to societal racism. Along these lines, then, if one wanted to know whether a political party or any other social category has an unusually high problem with a racism within its ranks (given that all will have some), it is not enough to point to an instance or two. Instead, we need to ask whether the prevalence is any higher than society at large. Unfortunately such figures aren’t produced very often, for one reason or another. When they are, it is often part of the political dynamic of trying to cast a group in a bad light. When the BNP looked like they were going to gain some success in the 2009 European elections much was made of how much of their support was drawn from people with problematic attitudes. So the anti-fascist campaigning magazine Searchlight said ‘amazingly one third of BNP voters agreed or partially agreed’ that there is ‘a major international conspiracy led by Jews and Communists to undermine traditional Christian values’. However, no media reported on the wider findings in which a large number of the voters of all parties agreed. Given that the number of voters for the main parties are larger, most of those agreeing were Conservative and Labour voters. Taking the YouGov poll and combining it with the numbers who did vote for these parties, it suggests the following: What this tells us is that there should be about 310,000 BNP voters who believe (to some extent) in ‘a major international conspiracy led by Jews and Communists to undermine traditional Christian values’ but about 1.5 million mainstream voters who will answer the same way.

Similarly, Tim Bale’s more recent research found that ‘some 13% of UKIP voters said they would be less likely to vote for a party with a Jewish leader… only 7% of Conservative voters said the same… for the Liberal Democrat voters, the figure stood at 6% and for Labour 4%’ (The Conversation). To me this is not surprising: preferring ‘people like us’ is normal for the middle-class and middle-aged, and so there will be more less-ideological antisemitism wherever we find people like this. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine that any particular party doesn’t have members with more ideologically developed antisemitism. The Green Party has had its own issues in this area (see here) as has the Conservative party (see here and here). In my own research, I was once present at a meeting in which a serving and senior Conservative councillor argued that all debate on Israel/Palestine is impossible due to all the main parties being funded by a Jewish lobby. The bigger sociological question, though, is how this is all connected, in terms of how ideologies of racisms are contoured in society, how ideologies (common-sense and developed) are understood and delineated into acceptable and unacceptable, and how the understanding of social groups and institutions become part of how racisms are understood and studied. First, the implicit association test shows that everyone, or almost everyone, is prejudiced to some degree, but we know that most people’s racisms do not lead them to extremism or violence. We should then ask how the everyday casual racism of the average person is connected to more problematic forms both in terms of ideology and transport through society. Second, society or parts of society judge racisms to have varying degrees of harm, and this is to some degree independent of any objective measure (e.g. whether violent or not, whether leading to discrimination or not). Some racisms are subject to little censure, some are beyond the pale, and such judgements arise out of the socio-political dynamic of national ideology and common sense and a range of oppositional forces. Third, understandings of social groups (‘race’, religion, class and so on) are often the basis for how we study and interpret racisms, including ideas about uncouthness and sophistication, workplace cultures and so on. So an ideal sociological research programme on racisms would be interested in polite middle-class or dinner party racisms (including antisemitism and Islamophobia), as well as the less polite, especially where such people hold political, economic and cultural power. On Armistice Day, 2010, as the nation's leaders led two minute's silence at the Cenotaph, just a couple of miles away in Kensington, two groups of 'extremists' faced each other. The first group, 30 or so radical Islamists from the group known as al-Muhajiroun or Muslims Against Crusades, began shouting 'British soldiers go to hell' as the nation’s silence began. Watching them was the second group, a similarly small group of the counter-Jihad or far-right English Defence League. Police officers and news photographers separated the two groups. However, despite advance notice, the two groups together didn't manage to get a hundred people to turn up. Further, nobody was hurt, and no serious crimes were committed. Why, then, did the radical Islamists' burning of a giant poppy, done to wind up the far right and wider society, make headlines and force government to take action?

Taken at face value, policies that ban al-Muhajiroun and restrict the English Defence League are done to stop the disorder and violence associated with their activities, particularly at set piece clashes such as this. Such policies may also prevent angry words from persuading people to extreme actions, including terrorism. Some individuals have moved from 'non-violent extremism' to violence and terrorism, including the killers of Lee Rigby and the Soho bomber. However, these individuals are a small proportion of a small pool of activists. Many activists, even those who glorify violence, don't want to get their hands dirty themselves. Drawing on Eatwell's ideas of 'cumulative extremism', I argue that counter-extremism policies demonstrate a further concern: it is feared that the provocative actions of these groups - including demonstrations, poppy and Koran burnings, mosque invasions, and Muslim patrols - prompt a reaction from others not already involved. Restrictions on speech and actions are made to avoid riots and communal conflict. Underlying this latter fear are assumptions about community and culture which contribute to a self-fulfilling prophecy. Standard explanations for the existence of radical Islamism and the far-right are made in terms of 'Asian Muslim' and 'white working class' communities being separated, and having cultures that facilitate hatreds. Such explanations simplify the range of opinion within these segments of society and posit particular 'communities' as uniquely suspect or problematic. When those in power promote 'British values' they place a range of attitudes (homophobia, racism, religious chauvinism) and behaviours (gender segregation, veiling, flag flying) on the extremist spectrum. Thus, they add credence to the idea that Britain is seeing a local version of the 'clash of civilisations', where Islam and 'the West' are incompatible. This, of course, supports what the extremists themselves argue. In my own work I argue that such explanations do not explain, and unfairly malign vast swathes of British society. Those engaged in real extremist activity are a tiny minority, and most people condemn them. Nor is there a sharp divide between sections of society fully subscribing to 'British values' and other sections which do not: survey research finds the presence of racism, homophobia and other intolerance everywhere, and tolerance can be found in all sections of society. We also exaggerate problems if we describe 'normal' but old-fashioned 'isms' as extremism. Most problematic, however, is the media's presenting of particular extremist individuals (for example Anjem Choudary, Nick Griffin, Tommy Robinson) as representative of whole communities or wider currents of thought, instead of the outliers that they are. Mona Chalabi’s Is Britain Racist? (BBC 3) was most entertaining and raised some interesting questions. As someone who has been a sociologist of race and racism for a long time, little was new to me but it’s good to see it done in a way that a non-expert public can relate to, and also without the over-the-top doom-mongering that some pop-TV approaches have taken. It pointed out that perhaps everyone carries around racial stereotypes, and so is then ‘a little bit racist’, and did this without condemning the public.

This was particularly effective when the presenter herself found that the Implicit Association Test showed she had a slight preference for ‘white’ faces over ‘black’, despite her own skin. When this upset her, being surprised that societal images had moulded her own mind, I laughed as me and my colleagues would expect exactly that. Indeed, in some studies even those who are ‘black’ are found to be racist (in one way or another) against others who are ‘black'. This then raises the question, implicit in the title, of what exactly we mean by racist. Others (in particular see Back, Crabbe and Solomos on the racist/hooligan couplet, 1999) have pointed out that seeing racism as something that only exists in particular deviant groups is a gross simplification that ignores wider societal issues. I’ve also argues that this conveniently gives the dominant culture, whatever that is, a pass: ‘we’re not racist because it’s the BNP/ skinheads/ the white working class (delete as appropriate) who are racist’. Given that the facts on the ground have never supported this, accusations of racism can be just another stick to beat marginalised people. But to say that racism is everywhere (including in minorities) can then be interpreted as though it were a natural fact of life, and either no-ones fault, or inevitable, and no-one population is more likely to be victimised or victimising. Thus a question like ‘Is Britain Racist?’ is much the same as the question ‘Is Britain Wet?’. To some extent, humans hold racial stereotypes and prejudices, some act on them and some do not. As Mona points out, we are products of our cultural surroundings. Britain is populated by humans, therefore… The real question, though, is what does this mean, both in terms of texture and trends, and this is exactly where some of the experiments done on the show, and the other data mentioned, actually shows something interesting. So we see that a ‘black’ young man gets stopped by shop security more than others, because society prejudges that a female in a hijab wouldn’t steal from Boots. When the female dons a face covering she gets random abuse from strangers. And even the liberal young people of the Pub on the Park (one of my favourite places) come up as having some prejudice in the IAT. But what does this add up to? What are the trends? Thus, it’s important to note that, while there is a background of pervasive societal racism(s) – including positive prejudices, what happens is a result of the individual actions that result. We have to think about motive, contexts, actions, and impacts. There’s a difference between a deeply held racist mindset resulting in an attack, and an unthinking prejudging that results in a faux pas. Indeed, racist incidents need not be motivated by racism. Bernard Guerin shows how even a well-meaning decision to challenge prejudice can end up as a racist event: one example would be not offering a hand to a woman who you have prejudged to not want a handshake, where in order to avoid awkwardness (i.e. taking her feelings into account) it ends up as a discriminatory act (Guerin 2006). Positive stereotypes – a group is better at sport, maths, whatever – are still discriminatory. An assessment of British racism needs to be a full picture of all the incidents, with different forms of racism present, even including those prejudices against dominant groups, while keeping in mind that this is all structured by a national culture (itself varying across time and space). And it is this last point that points to the most important question. We can assume that culture and society changes over time, through the population changing (births, deaths, migrations) and through individual change. This change need not be linear and straightforward: there is nothing contradictory about a society where the average level of tolerance for others seen as being of another kind is increasing, but racist attacks are also increasing. If 80% of people have become less racist (but would never have been obviously racist anyway) but 20% of people have become more racist, we will get indicators going in opposite directions. Any analysis like this has to be comparative too: hence Is Britain Still Racist? is really a question about whether Britain is less racist or more racist than other places, or other times. The most interesting part for me, however, was about the way that individual experience can create change. So Mona Chalabi spent some time imagining she was black, and then was tested as having a lower unconscious racial bias. Her final point was that thinking about how racism works, being more honest about how much it pervades social life, and so talking about behaviour and behaviour change might make people think differently. On this, I wholeheartedly agree but know that it takes effort. Furthermore, and returning to Bernard Guerin, this needs to be done by noting racist incidents without assuming ‘racists’ (stereotyped as unreformable, beyond-the-pale individuals) and ‘racism’ (as an accusation to be made at parts of society the powerful don’t like). Only with goodwill and trust will people be willing to admit problems and not be resistant to change. A long time ago I did a first degree in the Natural Sciences, and in the 3rd year I did a whole year of History and Philosophy of Science. I'd argue that this would be a useful exercise for everyone at university, as a bridge between humanities and science, as an education in how human civilisation developed over the millennia, and how we conceptualise knowledge and reality. On this latter point, I always feel thoroughly depressed when I see social research methods text reproduce a hackneyed 'positivism' v 'interpretivism' debate, when philosophers of science have left this long behind (in my opinion there is no inevitable great divide, except one we have created ourselves), and the practice of natural science is and was never as simple as hypothesis testing via experiment.

Anyway, all this came back to me while I was investigating a question in the Citizenship Survey. This survey was short lived, being part of the Labour government's response to 9/11 and the 2001 'northern riots'. As now, it was argued that a lack of 'community cohesion' is a risk factor for community conflict - that seems a bit circular, but never mind - and hence riots and Islamist/ far-right terrorism. The survey aimed to examine community cohesion and conflict through a set of questions on volunteering, community involvement and knowledge of/ attitude to violent extremism. One of these questions, which looks like it directly fits with the 'contact hypothesis' (Allport 1954), asks: · how often, if at all, have you mixed socially with people from different ethnic and religious groups to yourself…..at your home or their home? [and variations on this, including 'at work, school or college' and 'at the shops'] This question is a good example for thinking through what the data tells us, what it can be used for and perhaps why the data was created. All this should begin with some thoughts about what the individual's answer to this question means, and so how the question is understood and relates to real lives. One obvious critique of this question is the usual 'social desirability' problem: given the narrative about not mixing socially as being symptomatic of the stigmatised position of racist/ghettoised, it's likely that some will exaggerate their 'mixing socially'. I suspect that Muslims probably (on average) feel this pressure more than others, but I could be wrong. This is made all the more problematic by the reliance on memory - it's easy to 'remember' the right answer. More important, though, is the understanding of 'mixed socially' and 'different ethnic and religious groups to yourself'. The former phrase has an explanation in the interview: · 'By 'mixing socially' we mean mixing with people on a personal level by having informal conversations with them at, for example, the shops, your work or a child's school, as well as meeting up with people to socialise. But don't include situations where you've interacted with people solely for work or business, for example just to buy something.' This is a bit confusing, in my opinion. Many, or perhaps even most, situations could be interpreted as both. I go into a shop to buy a paper, and have a chat with the guy behind the counter about the news: this is both 'just to buy something', and 'an informal conversation... at... the shops'. I talk to another parent about the school-run traffic: this could be solely for the business of fetching children, with no sociality beyond this. The latter phrase is, for me, even more problematic. It requires a judgement of one's own 'ethnic and religious groups' and that of others, and this can depend on the level of importance placed on such identity. As an atheist, would I count all religious people for this, and would I even know if they are religious? I could play football with someone who goes to church or the mosque and not know as it's not a conversation we'd have. Would a Catholic have to count a Protestant? Or a Shia Muslim count a Sunni? Do English people count Scottish people as a 'different ethnicity' or Tamil people count those from the rest of India? My theory is that those who take a religious identity more seriously will be more likely to know the answer, whereas someone who has no religious identity may well 'mix' but hasn't registered it. So it's possible that the aggregate data here shows a pattern different to any underlying contact. Even if we think that the question is actually understood/ interpreted/ answered in the same way across the population, we also have to think about what any answers actually tell us. Yes, a bald figure of who says they socialised with who and when may not be an exact correspondence with reality, but perhaps we can use it for comparisons. However, even here there are problems due to all the other stuff going on... My first question would be how this compares to socialising in general: after all, any 'mixing socially' with those deemed different (by the survey) ought to be seen in the context of all 'mixing socially'. Someone who doesn't answer affirmative here might not do much socialising in the home, full stop. It reminds me of the reasons why I was out on the street every night as a teenager: I didn't have private space at home for socialising, being in a two-up, two-down terrace where my bedroom was where the kitchen would normally have been. Second, what's 'normal' will vary for a multitude of reasons, some economic, some cultural, some geographical and so on. Living in a County Durham pit village will create different opportunities for sociality than Newcastle city centre. Data like this might say something if we can compare like with like, but no two environments are exactly the same. Thus, the theory laden-ness of data and data creation comes back when the analysis is done at the end. The survey was created for particular circumstances - particularly the fear that white working class and Asian Muslim 'communities' are divided (see Ted Cantle) - and the questions reflect that. Similarly it's possible to analyse the data for this theory. However, perhaps an ethical sociology should approach the data in a different way... before jumping to conclusions and checking whether the white working class and Asian Muslim populations are somehow uniquely different to the rest of society, we should check for other explanations, through thinking about the data more creatively. That's not to say that this quant data is irrevocably flawed, but that like any data it is created in a particular process and context, and that this needs to be considered very carefully. I'm only noting this strange contradiction today, with a plan to expand on this once I'm on a break from work...

On the one hand the government's forthcoming counter-extremism strategy: 'is... said to claim the Trojan Horse affair - which looked at allegations hard-line Muslims were trying to gain control of schools in Birmingham - was "not an isolated example of schools where extreme views became prevalent".' (BBC News) On the other, the Conservative chair of the Education Select Committee said: 'apart from one incident, no evidence of extremism or radicalisation was found by any of the inquiries into any of the schools involved.' (Guardian) I've long enjoyed Jon Ronson's writing, and it's probable that it was his TV show about extremists, and the associated book are what inspired me to hang out with al-Muhajiroun, BNP, and EDL activists over the years. This last week or so I've been reading the various extracts of his new book about public shaming: while it might seem like a very different topic and approach, I see connections between how extremists have been opposed in recent years, and the random destruction of individuals Robson describes. In both cases the political is reduced to simple one-off facts, which can be fitted into an easy to understand narrative. What we see, then, is the power of the datum.

The power of data used to be in its combination. A survey might combine 1000s of respondents to create a picture of the various relationships between social facts: individually they might be decontextualised, but data works together to create patterns for us to interpret. A biographical interview should combine lots of data about one person to create a context for understanding what a person is about. Similarly, a historical study uses the available data to create a picture of a time, a movement, a battle or a political party. I may be hopelessly nostalgic, but I feel it used to be the case that this kind of analysis was necessary in order to make a full assessment of a person, a government, or any social phenomenon. Academic and journalistic writing would examine careers and trajectories: asking what did someone say or do, and why, who to and what for. When it comes to the far right, say, good studies looked at the history of a party or an individual. They would examine change and continuity, cause and effect. It seems that in order to make the judgement that the thing in question is fascist or racist or any other ‘ist’, one needs the full facts of the case. Quite rightly, though, this approach can be critiqued because groups, events, and people are not consistently one thing or another. It is harder to categorise something as X, when a full description demonstrates it to be internally contradictory. Even for an individual incident, we can ask questions about the motives of the speaker or doer, and how it is interpreted. I’ve long appreciated the idea of Bernard Guerin in ‘Combating everyday racial discrimination without assuming racists or racism: New intervention ideas from a contextual analysis’, in which we can see incidents that are racist, without attributing the cause to some internal racist property of the person. Guerin sees ideas of internal properties as unhelpful as they essentialise, lay blame on individuals and not the social, and don’t make for good interventions. I think it also relates to David Oderberg’s thoughts about those in a liberal society feeling that they shouldn’t be judgmental. But… we don’t want to fall into the trap of never judging, of being the moral relativist who can’t see right from wrong. This, combined with both the way that modern technologies record, splice and flatten each time and space instant, as well as the assumption that we cannot fully understand that instant, means we have chosen to make judgments based on single, verifiable, transmissible - and decontextualised facts. Jon Ronson calls it the ‘war on flaws’. For me, this seemed to begin with opposition to the extremists. When the membership of the BNP became bigger, it began to include people who weren’t interested in fascism, and many of them weren’t even particularly racist (and no more so than those in other parties). They were drawn to anti-immigration and anti-multiculturalism politics, and a party that was, according to Goodwin, attempting to ‘modernise’. Furthermore, the idea that individuals were somehow synonymous with parties had already broken down, so these BNP activists were hard to attack on the grounds of mere belonging - they were ex-Labour, ex-Tory, ex-everything, so if they were long term ‘bad’ then they were bad for the main parties too. Thus, attempts to discredit became based on individual instances - where people had said something outrageous, and ideally something that would be expected if they were a fascist or a racist. Instead of doing the impossible of examining someone’s heart or character (a la MLK), or judging a longer record which again might be inaccessible, we could judge on the single fact. This was extended, famously, to UKIP in later political campaigning. Individual activists would be outed for something they said (on one occasion something they said as a Conservative councillor), and although the particular words may have been also said by people in other circumstances, they were deemed indicative of their UKIPness (i.e. presumed racism or anti-immigration attitude) and used to discredit them. Now, however, this approach is everywhere, and has become a Hobbesian war of all against all, with an appeal to an assumed universal rightness of the mob. It’s also able to transcend time, because almost all of us have long-term public records on Facebook and Twitter. I’m assuming that most people have said stupid things, or used inappropriate words at some point. Shouldn’t some of this be forgotten, and individually we can remember, be mortified and try to not do something so silly again: maybe it was an accident, a misunderstanding, a didn’t know not to, or a deeply buried attitude that isn’t usually expressed. And maybe it was a joke… The Justine Sacco tweet Jon Ronson writes up was. It was only one tweet, as opposed to a lifetime's work, and would be better judged as part of and in the context of everything else she's said and done. I think there are two important points to consider in this example, one being how the one example has been decontextualised, and the second about the way that the decontextualised example is drawn into a particular political debate where comparisons are legion. We seem to be in a position,perhaps due to the way technology allows data to flow freely and preferably in tiny chunks, where combinations of words are judged purely in themselves. So a phrase or wording used becomes detached from the motives of the speaker and the context it was used. So when Sean Penn said 'Who gave this son of a bitch his green card?', there was much commentary about how he or it was racist. It's my belief that this was an anti-racist comment gone wrong. Some have noted that Penn and Alejandro González Iñárritu are good friends, and it was the kind of banter they would get up to in private. This defence misses the point. It probably is necessary for them to be friends for this to work, but it could be set up with someone the speaker trusted. This isn't sufficient, however. The more important point is that the line was meant to be public, was meant in a particular way, and this only works with the context. That is, we know that Penn is a liberal activist, and that he knows about anti-Mexican sentiment and discrimination, that this is often spoken of in terms of green cards, and he opposes it. He repeats these words to draw attention to them, he's paraphrasing the racist, doesn't agree with it, and is using the fact that González Iñárritu is super successful to show why the words are wrong. He's doing what we call in the UK 'taking the piss': we must remember that people say things they do not mean because they are being ironic or sarcastic. In Britain this is the basis of a great deal of everyday talk and TV comedy: satire is a national sport, and as Will Self puts it, we have 'a commitment to never saying what you mean, but only indicating it to those who are in the know'. For some viewers this evidently fell flat, and anti racists can claim that either he's demeaning the cause or perhaps making a distinction between poor migrants and his friend. There may be some who misunderstand because they don't know the context, or understand it but feel that others won't get it and it will create more ill feelings, or wilfully misunderstand it to make a point. Similar issues come up all the time, with slightly different threads to pull at. The row over rape jokes is a case in point. Here, it seems that the original words need not be dissected, with the spreading of the datum and argument being, X comedian made a rape joke... rape jokes are never acceptable... X should be admonished. But comedians will argue that nothing should be off limits, and there can be good jokes about rape. Sarah Silverman's is a good one, and some would ask if this would be OK I said by a man. Again, this misses the point: a woman could make a nasty rape joke, a man could do this joke. It's the total context that matters, and the identity of the speaker is just a shortcut. Comedians are able to say the opposite of their own opinion, with the audience understanding this, because of a shared history. The second point relates to the way such pieces of data are drawn into a political debate. Somewhere I saw someone comparing the Justine Sacco case to that of feminist activists being trolled or otherwise abused. In some respects this is valid: it's the same herd or mob mentality. But it's very different with regard to who's doing it to whom. For those already engaged in the political debate, battle lines are already more or less drawn. So the feminist activist will write her (rarely his) piece and will be attacked by anti-feminists, usually men. But this is based on expressed and genuinely held beliefs, and those attacking and defending are genuine enemies. Those who are taken out of context or picked up for a flawed moment are not necessarily on the opposite side or any side, but are attacked nonetheless. Sacco didn't expect to be in this dynamic at all for her joke. Sean Penn was attacked by potential allies, or those who he could ally with. Penn, of course, is doing well enough to laugh this off, maybe avoiding putting a foot in it on future occasions. Those engaged in political battles will just be hardened. However, I'm interested in the response of the average Jo... Many will be reluctant to say anything again of this kind, avoiding getting involved in case they say the wrong thing: the twitter mob have lost a potential ally for their views, if not their methods. Others may be bounced into an opposing position, creating another person who can join the trolls, angry that their flaws were blown up out of all proportion. It seems to me that the prosecution of Dhanuson Dharmasen for Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) was all a bit cack-handed, to say the least. Possibly politically motivated, timing wise, it does seem to be a demonstration that 'something will be done'. It reminded me of The Wire, and the moment when politicians need results, put pressure on commanders, who then ask their people to do something to get the figures up for this week/ month/ year. To these ends we end up with a few street dealers arrested, a load of drug users arrested, and the police have to forget about going after their bigger targets. Indeed, this activity might even undermine bigger operations.

In instances like these, those in power go after the low hanging fruit, the quick win. In the case of the doctor, they had a case - what was described in court could have been judged illegal as the FGM law does prohibit reinfibulation, and even the one stitch could count even if the motive wasn’t for FGM purposes, as long as it was not a ‘necessary surgical operation’ - but more importantly they had evidence. The single stitch was done by an NHS doctor, in one of the country's most famous hospitals, and the doctor asked a senior colleague if he'd followed the correct procedure, having been trained to deliver babies, but not on what to do if the mother has complications due to childhood FGM. Records were kept, and witnesses were reliable: little investigation needed to be done. The FGM incidents that society wants to prosecute, however, aren't like this. They're done by backstreet surgeons, or arranged by families that take their child elsewhere to get it done. Presumably these incidents are not logged by any bureaucracy but are kept secret. The only witnesses do not want to talk. They might be in favour, in fear, or just want to keep the family together. The crimes may come to light years after they happened, so getting proof of who said and did what is much more difficult. It's no wonder that prosecutions are difficult. A genuine anti-FGM action requires a lot more than legislation. It's cheap to pass laws, and expensive to actually enforce them. Like The Wire's major investigations, a good prosecution would need undercover work, maybe some communication interception, and certainly some people willing to talk from the inside. Resources, mainly 'man-hours' have to be allocated: the work has to be prioritised. Given that current estimates are that the police budget has been cut by 20% over the last 5 years, something would have to give. Who'd like to make those choices? Going after FGM crimes? Rape? Burglary? Terrorism? Fraud? In recent years, as I've gone about my work I've been misrecognised as:

1. Jewish 2. Arab 3. A far-right activist 4. A far-left activist What this tells me, I don't know. I haven't deliberately tried to look or act like any of these, as though there is really a stereotypical way of being X anyhow. I think that it's all about expectations - if you're getting on with someone then they think you're from their background, if you are doing research then you're oppositional or supporting. In reality, the only thing that I am is nosey - always was, and always will be. |

Archives

May 2022

Categories |